Sad Things Happen

Circuses, regeneration, and dissolving into history

A foreign circus proprietor expires suddenly in an industrial city south of Stockholm, and his circus – bankrupted by being split between expensive venues in two locations – limps on for a few more performances and then scatters. His two young nieces leave for Prague to become greater stars – one ends up a baroness, the other is mortally wounded in the ring – and his widow, once famous, is pitched into retirement and obscurity. Some performers try to make a living giving concerts or throwing impromptu performances in other Swedish cities. Others head abroad to join new circuses, looping back into a familiar life and dissolving into history. One ten-year-old child performer, however, goes on to a darker, notorious fate. I’m going to write about her a little today.

The circus proprietor who died unexpectedly in Norrköping (either from a kick from a horse or a poisoned abscess, depending on your news source) was François Loisset of the eponymous circus dynasty. At the time, his equestrian “Cirque de Paris” was touring with some fifty horses plus a donkey called Rigolo II. Spectators could win 5,000 öre if they managed to ride Rigolo II three times around the ring without being bucked off (a cheap seat was 50 öre, so this was quite a prize). With François was his wife, the first famous haute-école equestrienne, Caroline Loyo. Their nieces Émilie and Clotilde Loisset were the headline stars: Émilie was sometimes joined in a haute-école duet by her sister, but mainly Clotilde was dancing and leaping on horseback. The Swedish king and crown prince had taken Prince Friedrich of Prussia to watch them perform in Stockholm.

On the surface, everything had been going well, but when the king pole was removed, the tent collapsed. Even the 3,000 krona in cash and valuables François had had on his person vanished. Émilie and Clotilde had a benefit performance in their honour in Stockholm, supported by a rival circus, with the Swedish and Portuguese foreign ministers in attendance, and then they were off to Prague with Salamonsky. Caroline buried her husband in a Catholic cemetery in Stockholm and evaporated from the news, retreating to provincial Bléré, where I think she had family. She does not resurface in French newspapers till an army officer runs into her in an inn where she is eating the prix-fixe lunch, and “interviewed” her for the press.

But what about the ten year old child? She had debuted with the Loisset circus in Copenhagen the previous year as “little Hedwig” in a pas-de-deux on two horses with her stepfather, the American John Madigan. Now she was touring Sweden. John Madigan performed a double “salto mortale” – a leap that can result in death – and also somehow leapt over eight horses. He alternated performing the pas-de-deux with Hedvig and her mother, who went by Miss Ulbinska but was really called Eleonora Cecilie Christine Marie Olsen. When the Loisset circus fell apart, the Madigans joined Circus Ciniselli and Hedvig gave up horses for what would prove her greatest talent: slack-line walking.

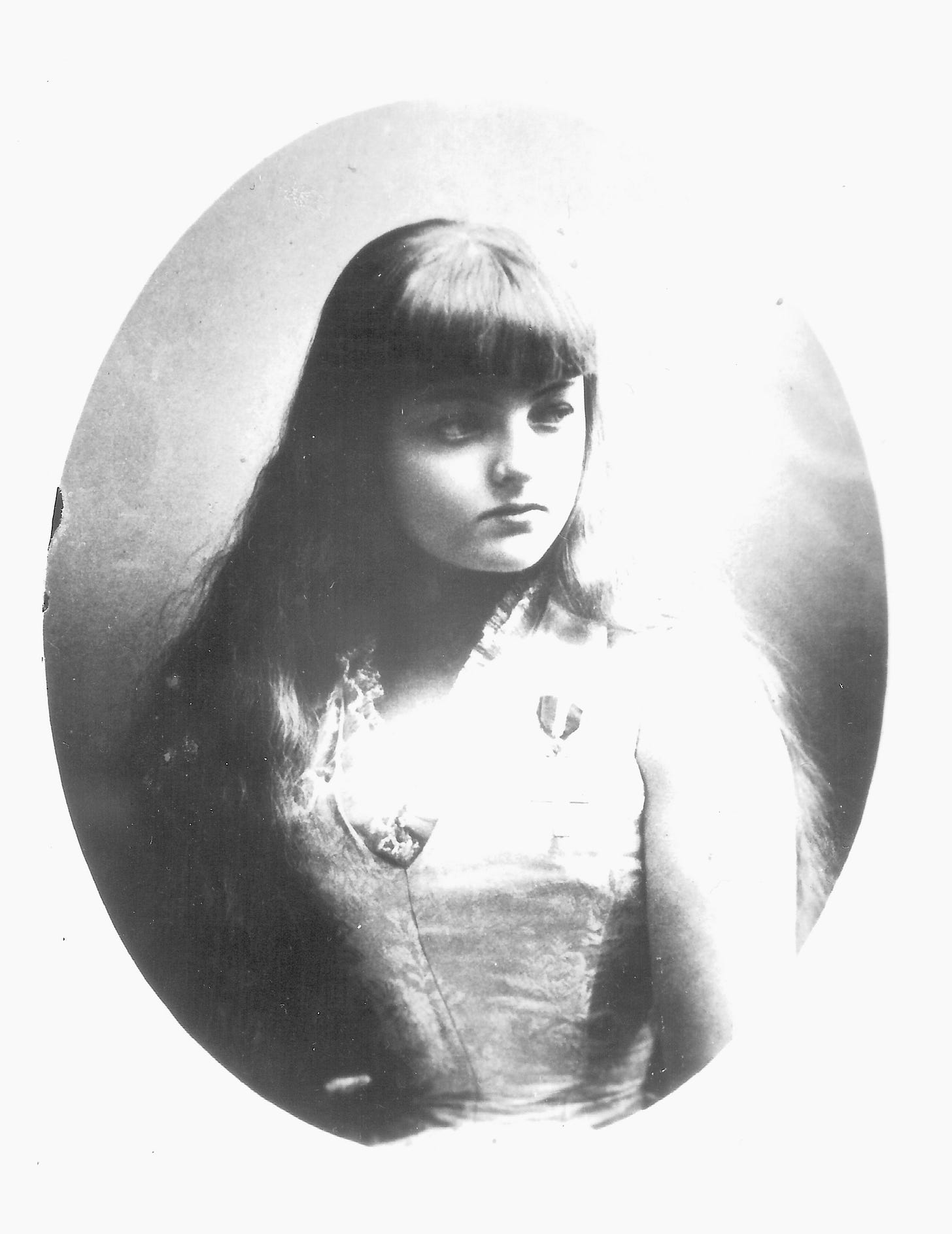

Over the next ten years she was on the road, performing in some of the most celebrated circuses in Europe and Russia. She changed her stage name to Elvira Madigan. She was beautiful, with a round doll’s face and long blonde hair, and usually worked with a tight-rope dancer called Gisela Brož, one rope suspended above the other over the ring, slack and tight, the young women dancing, balancing, juggling in parallel.

Elvira’s life might have tracked that of so many other circus performers – a stiff existence on the road in the circus bubble till injury or age forced retirement – but instead it was derailed. At Kristianstad in Skåne, she caught the eye of a broke, married Swedish aristocrat called Sixten Sparre. She was 21, he 34, a dragoon lieutenant who had married for money and burned through his fortune. It was January 1888. Sparre was infatuated, and began a secret correspondence with Elvira, neglecting to tell her about his wife or debts. The newspapers of the time called what followed a “drame d’amour”. You might also call it “folie à deux”. In 2025, I think we would see it as coercive control.

Elvira tried to end the exchange of letters; Sparre told her he would kill himself. Elvira broke, then eloped with him in May 1889. She packed her all. Sparre packed a few clothes and a loaded revolver. The couple went on the run first to Stockholm, pursued by Elvira’s mother, and then to Denmark. They left a trail of unpaid bills behind them and a gathering scandal: Sparre had deserted the Swedish army and faced execution for this, and he had drained the inheritance of both his children. He had borrowed money from friends and left the rent on the family home unpaid for eighteen months.

On the 19th of July, in a forest at Nørreskov in Denmark, Sparre shot Elvira and then turned the gun on himself. Their bodies were found three days later by an elderly woman who was picking raspberries. Their deaths came seven months after the murder-suicide committed by the Austro-Hungarian crown prince Rudolf at his hunting lodge in Mayerling, just outside Vienna. The prince’s victim was his 17-year-old mistress, Maria Vetsera. Sparre and Madigan were soon the subject of debate in the Scandinavian press and of a popular ballad, “Sorgeliga saker hända” or “Sad Things Happen”.

In the twentieth century, their story inspired films in 1943 and 1967. Recent biographies by Klas Grönqvist and Sparre’s great granddaughter, Kathinke Lindhe, have revised the love story: Grönqvist believes Sparre was bipolar. Meanwhile, the story had been so buried by Lindhe’s family that her father only found out when he was watching the 1967 film. “Sorgeliga saker hända” was banned in their family home over half a century after Sixten’s death. Lindhe found the lieutenant’s financial paperwork in her attic and totted up the full extent of his debts; Sixten’s widow had been left penniless.

There was a poem in Elvira/Hedwig’s pocket, signed with her real name. It was written in a mélange of Swedish, Norwegian, German and Danish. It spoke to me about the entire mission of Amazons of Paris, of finding the lives dissolved in the sea of history:

A drop fell into the water,

faded out slowly.

And the place where it fell

surrounded from ripple to ripple

What was it that fell?

and where did it come from?

It was but a life,

and but a death that came

to win itself a track.

– - –

† Now the water rests once again.

Sources

For details of Elvira Madigan’s life, I used Wikipedia.sv, which makes plenty of use of Klas Grönqvist’s book, Elvira Madigan: en droppe föll (Recitor Förlag, 2013). The English translation of her poem comes from the English Wikipedia page but has no credit. I changed the word “wave” to “ripple” but a more elegant translation is beyond me without Norwegian or Danish! I’m happy to add a credit here if one can be found. I also read about Sixten Sparre via this interview with Kathinke Lindhe. Her books on the subject are Sorgeliga saker hände – Elvira Madigan, Sixten och mig (Utblick media, 2014) and Vacker var han, utav börd: Sixten Sparre, mannen som mördade Elvira Madigan (Ekström och Garay, 2021).

Surprises

I just learned that John Madigan is buried in my hometown of Lund. There is still a “Cirkus Madigan”, founded in 1989.

Extra extra

You can read my Paris Review Daily essay on Émilie Loisset here, though I have discovered more about her life since then.

Variétés

I briefly mentioned a rival circus in Stockholm that joined a benefit performance for Émilie and Clotilde Loisset after François’ death. This was the Léonard Circus. I found a bit of Swedish press about the fact that they were competing with the Loisset circus for audiences. Then I remembered where I had also seen their name.

This summer I bought Privat Flickan, a novel by Swedish journalist Evelyn Scala Schreiber. It’s about an actress who falls in love with a circus rider in the last quarter of the nineteenth century so I thought it would be the perfect read to develop my Swedish. I reckoned without the workload for my current course though, so my progress is somewhat slow, and I can’t tell you how the Léonards fit in yet, but I will get there bit by bit.

Scala Schreiber based the story on her own family history in the circus; it’s the first of a trilogy. There is no English translation so far, but it is coming out in German, Norwegian, and Russian. You can find out more here.